Maybe it’s time to retire the idea of “going viral”

For years we’ve been using the phrase “gone viral” to describe something that becomes wildly popular on the internet. But it strikes a different note in the middle of a global pandemic, especially when the viral content is about an actual virus that is killing people. It’s even worse when you’re talking about “viral” content containing dangerous misinformation and conspiratorial thinking about such a virus—like Plandemic, the documentary that got millions of views on Facebook and YouTube last week before the platforms started removing it.

These past few months I’ve started catching myself whenever I write or speak about something “going viral,” searching for another way to put it. A couple of weeks ago, I started wondering whether we should even be using the word in this figurative way at all anymore. Turns out I am not alone.

“I’ve stopped myself with that expression,” Peter Sokolowski, a lexicographer and editor at large at the dictionary publisher Merriam-Webster, told me. Then Sokolowski asked one of his colleagues, computational linguist Ben Mericli, to help figure out whether other people were pulling back on using the internet sense of “viral” as well.

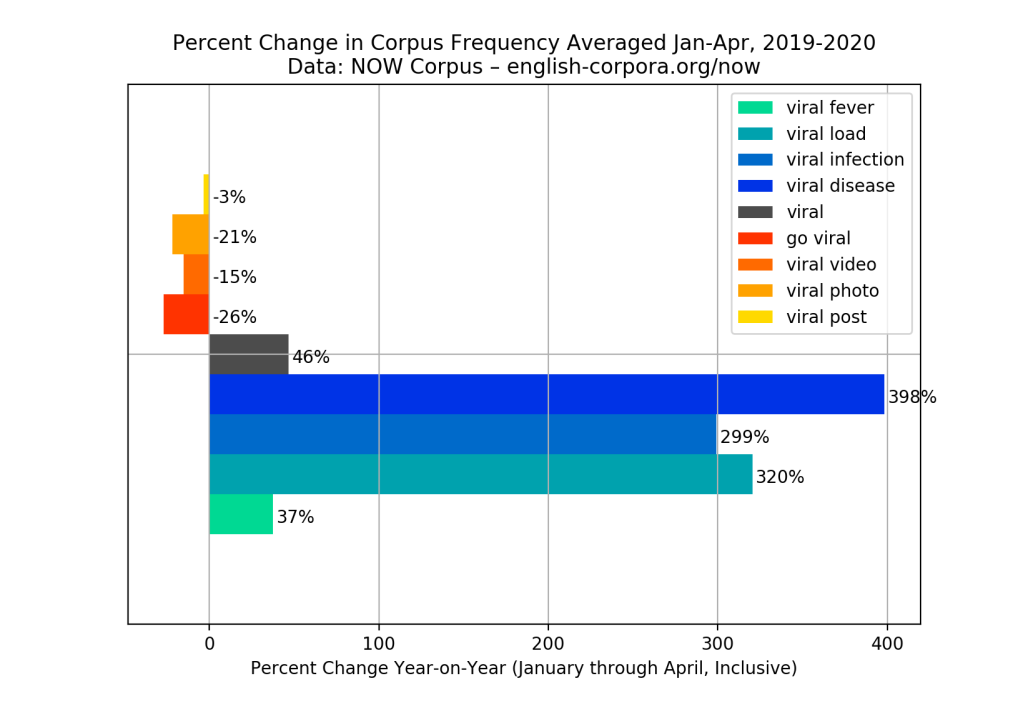

To do that, Mericli picked four phrases that usually refer to biological viruses (viral disease, viral infection, viral load, viral fever) and four phrases that usually refer to internet content (go viral, viral video, viral post, viral photo). He looked at their frequency in a large database of news articles from January 1 to April 30 this year and then compared that with the same period of time in 2019.

The results were pretty clear: figurative use of “viral” has clearly decreased this year as literal uses of “virus” have gone way up. “Since the outbreak, viral has just been used more often in general, with the increase owed entirely to literal use,” he said in an email. “So in that sense I suppose it’s even more striking that the figurative numbers are down.”

Although it seems logical, this decrease isn’t actually a given: plenty of words with medical or epidemiological origins are able to cohabitate in our language with their original or literal meanings, Sokolowski said. For example, both laughter and a disease can be “contagious” or “infectious.” Sometimes people don’t even realize they’re using a word with such roots.

“When people say vitriol they don’t know they’re echoing a chemical compound that burns human skin,” he said (vitriol was originally a term for sulfuric acid). But “viral” is different; the meanings are related but not the same. We have viral stories about viral infections, and we know what both mean. “It’s possible that these two words are used in such similar contexts in similar writing that it is a bad choice,” Sokolowski said.

But as I spoke to other people about their own usage, I realized that whether the current situation lasts or not, there are other reasons to question whether “viral” is appropriate language for content on the internet.

Manipulated popularity

“Viral” outrage, “viral” videos, “viral” posts, and “viral” moments have been part of the language of internet culture since its beginnings. The term itself comes from viral marketing, which started in pre-social-media times with advertising agencies that promoted whisper campaigns or tried to manufacture word of mouth. But once it shifted online, “virality” dropped the connotation of having been engineered by people who were experts at getting your attention and became something more accessible and democratic: a flash cartoon spread because it was funny, a fail video because it triggered schadenfreude, a blog post because it was insightful. “Viral” became a way of implicitly signifying that something was worthy on its own merits of sharing, of media coverage, and of your attention.

But this sense of emergent, authentic popularity isn’t necessarily real: algorithms incentivize content that people are going to engage with, accelerating its spread, and people have gotten really good at manipulating how social media works in order to spread bad or potentially dangerous material. There are plenty of examples, and despite efforts to stop the flow of extreme views and misinformation, the strategies designed to hijack your attention keep working. Deep down, people should know this by now.

Plandemic spread from the antivaccine fringes because there was a deliberate push for attention by coronavirus conspiracy theorists—who exploited the way social-media culture is intended to function. They were wildly successful. For the past several weeks, well-known antivaccine personalities have been attracting millions of views by giving interviews to other YouTubers with bigger followings, creating content that boosts right-wing outrage about the lockdown, and then using their well-established online networks to get that content shared widely.

“There’s nothing to protect you”

Whitney Phillips, an assistant professor of communication and rhetorical studies at Syracuse University, researches how misinformation and extreme ideas are amplified to reach bigger and bigger audiences, particularly by media coverage. She co-wrote a book with Ryan Milner this year that employs ecological metaphors—for instance, pollution—to help explain the digital universe in which bad information spreads.

“We need to think differently about our information ecosystem,” Phillips told me. “The metaphors we use can help shape our thinking on our responsibility.”

“Viral” could be a good metaphor for the spread of misinformation, Phillips told me, if only people used it correctly. “But they’re not,” she said. And that’s particularly true for the journalists who produce stories about trending misinformation.

“There’s this tendency to talk about it as if we stand outside it,” Phillips said. But we don’t: “If you’re writing a story about a particular disinformation campaign, you become a carrier for that virus.” Same goes for those who share it, whether to endorse, mock, or condemn. In other words, people may think they’re protected from the potential harm that misinformation on the internet can bring, but many are asymptomatic carriers of that information into spaces where it can devastate.

“There’s no PPE,” Phillips said. “It doesn’t exist. There’s nothing to protect you when you write about it and read about it.”

The discomfort that I’m feeling describing something like Plandemic as viral, then, has some grounding. But it’s not that the word itself is bad, or even that it’s an inherently insensitive metaphor, although it may feel that way right now. The problem stems from how we’ve fooled ourselves into believing that “virality” is something we can observe without being part of—that we’re immune to the problem of dangerous misinformation if we don’t believe it, when in fact we are the carriers helping it spread.