Doctors are now social media influencers. They aren’t all ready for it.

When President Trump suggested during a press conference that doctors should look into treating covid-19 patients with an “injection inside” of disinfectant, “or almost a cleaning,” Austin Chiang, a gastroenterologist at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, knew he had to react.

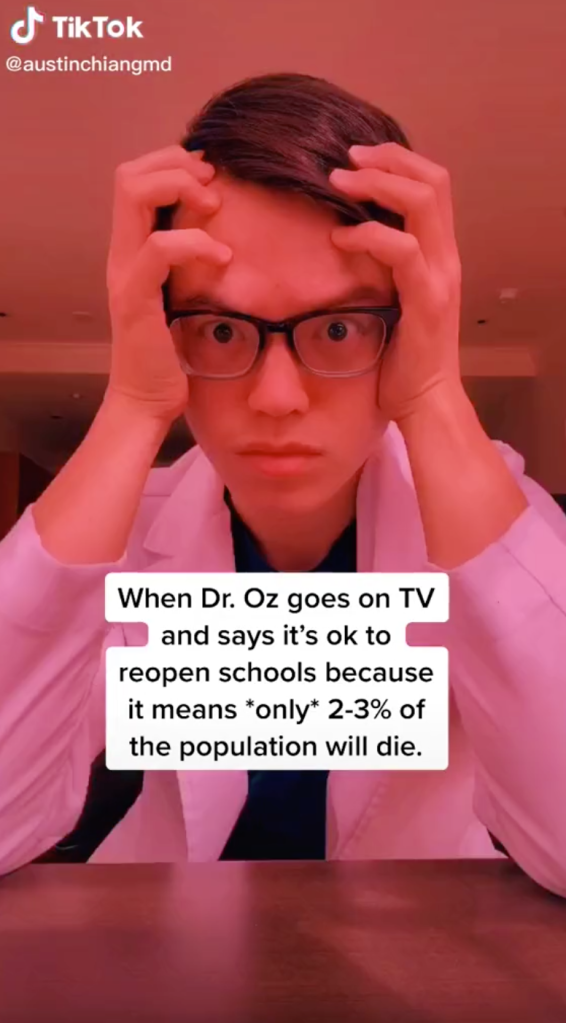

In his lab coat and scrubs, a stethoscope draped around his neck, and staring directly into the camera, Chiang sat in front of a news headline about Trump’s comments and mimicked screaming.

“I promise I won’t pretend to know how to run a country if you don’t pretend to know how to practice medicine,” Chiang wrote on the screen. The video, posted shortly after Trump’s comments, quickly gained tens of thousands of views.

Chiang is one of a new generation of doctors and medical professionals who have built online followings on platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Youtube. Their medical credentials give their thoughts on the virus added weight.

While doctors made famous by TV have had to apologize for downplaying the virus and suggesting that losing some lives was an acceptable cost for re-opening schools, some of the new doctor-influencers are positioning themselves differently. At their best, this wave of doctor-influencers can combat misinformation by making responsible medicine sound almost as exciting as the scores of medical conspiracy theories, exaggerated claims, and snake oil promises that spread rapidly online.

For some, it’s a gap that was waiting to be filled. Natural healing personalities peddling dubious information were “early adopters” of social media, says Renee DiResta, a researcher with the Stanford Internet Observatory who studies health disinformation. By the time platforms like Facebook and YouTube began cracking down on bogus health claims, they were already selling “cures” in natural healing Facebook groups, racking up millions of views on YouTube, and showing up in Google results.

“They sell their ‘cures’ using the same techniques that brands use to sell shoes,” DiResta says. “With an added layer of mystique via framings that suggest elite knowledge, like ‘The cure THEY don’t want you to know about!’”

Science-based medical professionals are playing catch-up.

The internet’s ‘black hole’ of expertise

“I actually think that the lack of quality physicians on social media has led to the rise of social influencers pedaling miraculous cures and detox teas and all that,” says Mikhail Varshavski, a.k.a. “Doctor Mike,” a family physician in New Jersey who has more than 5 million subscribers on YouTube. Until recently, he added, personality-driven medical social media has “just been sort of this black hole where doctors aren’t there because they don’t want to be perceived as unprofessional and as a result, misinformation thrives.”

But online fame for doctors and nurses comes with risks that are only heightened by the importance of their job. And as more and more medical professionals jump online to help guide the public and combat misinformation, there’s an additional risk that they become part of the problem they’re trying to fight.

The very things that help Austin Chiang reach a younger audience on TikTok can, if he’s not careful, undermine the trust his audience has in medical professionals. You have to be funny to connect on TikTok without seeming cringey or out of touch with the culture of the app. And you have to maintain that balance without crossing a line into unethical behavior. There have been, for instance, medical professionals who have used TikTok to mock their patients. And even those with the best of intentions and accurate information can find themselves in trouble when they move to a new medium.

“How do we present ourselves online without eroding the public’s trust in us?” Chiang told me. “There’s a lot of people out there who are new to the platform and who will throw something up there without thinking it through.”

Good intentions gone wrong

Take Jeffrey VanWingen, a doctor who runs a private family practice in western Michigan. He wanted to help the public when he stood in his kitchen before work, filming a video in his scrubs that he believed the world needed to see: “PSA: Grocery Shopping Tips in COVID-19.” It was March 24; the governor of his state was going to issue shut down orders the following day. VanWingen is not an epidemiologist or a food safety expert, but he did know sterile techniques that, he believed, could be modified to help people keep the coronavirus from coming into their homes along with their groceries.

Although he knew that the risk of someone getting sick from touching groceries was likely very low (grocery shopping’s main risk these days comes from the other people in the store with you), “even very low is not negligible. It’s not nothing. And, and I think my goal was to empower people to help keep their risk of acquiring covid-19 airtight,” he says.

VanWingen’s 13-minute video demonstrated procedures for disinfecting different types of food, as his calm voice guided viewers through dumping food into “clean” containers, disinfecting packaging, and washing produce. The video was shared widely on social media, and passed between friends in email chain letters, as a panicked public looked for something they could do to have some control over the spread of a terrifying virus. The video, the first ever on his month-old YouTube channel, gained 25 million views and counting. But the video is also, at points, misleading.

You should not, as VanWingen initially suggested, wash your produce in soap and water—it’s better to just rinse fruits and vegetables in cold water because soap residue can cause digestive issues. And his suggestion to leave groceries outside or in the garage for a few days before bringing them into your home needed a clarification that this would not be a safe procedure for perishable goods.

VanWingen lobbied YouTube to let him edit the video and remove the portion with potentially harmful advice, but there wasn’t much he could do aside from take the whole thing down. He decided against that, instead littering the video’s description with updates linking to new and more accurate information. But, he says, he still stands by the majority of the advice in the video.

“If you associate Dr. VanWingen with misinformation, that weighs on me extremely heavily,” he says. Compared to others, he says, his mistake was innocent and would be unlikely to have dire consequences. “There are doctors that I’ve seen that are promoting, like for instance, hydroxychloroquine and maybe even promoting fear,” he says, referring to the unproven and, according to the FDA, potentially dangerous covid-19 treatment that was promoted by President Trump. “That is certainly not where I would see myself coming from. ”

“There are doctors I’ve seen promoting hydroxochloroquine and maybe even promoting fear.”

And the people who can get views for a medical message on social media aren’t necessarily the ones most qualified to craft it. Eric Feigl-Ding, an epidemiologist who now has a large following on Twitter thanks to his evocative tweets about Covid-19, has found his expertise and analysis questioned by other epidemiologists.

Varshavski, that is Doctor Mike, became YouTube’s go-to medical expert after a 2015 Buzzfeed article about his Instagram account dubbed him the “hot doctor.” And although he often stresses to his audience that “expert opinion,” including his, is “the lowest form of evidence,” his viewers fans are more likely to trust what he says in his videos than they are to track down and read a randomized controlled study on the same topic. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, if the information is sound and clearly presented—and he described his role during the pandemic as essentially turning himself into a mouthpiece and platform for the CDC, WHO, and leading experts in the field.

But it’s easy to lose that balance.

“If you are a doctor and you’re popular and people look to you for guidance, and you believe your expert opinion without any kind of research to substantiate it outweighs that of the guidance from the CDC and WHO, you’ve crossed the line,” he says.

And that’s the central challenge: people will turn to the internet for information during a health crisis, whether it’s their own or one facing the entire world. But the best, most accurate information isn’t always packaged and optimized in a way that is appealing to a curious public searching for certainty. For every CDC video about the latest studies on the coronavirus, there’s someone out there claiming to be the one person out there willing to tell you what “doctors don’t want you to know.” That gets combined with a president who is amplifying potentially dangerous ideas so that they become significant news stories.

Doctors becoming brands

There’s another challenge faced by these doctor-influencers, too: branding and money. Personalities like Doctor Mike can make accurate information interesting by becoming influencers, but they also have to figure out a way to do that without falling into ethical quicksand.

People become famous online by becoming human brands. But “turning ourselves into brands can also drive people in a different direction,” said Chiang. “Some people out there are aligning us with big pharma already. The last thing they want to see is that we are selling a product or idea.”

Varshavski, like many content creators, takes sponsors for his Instagram and YouTube accounts, but said he has to make sure that those sponsorships don’t look like medical endorsements. Chiang, who also serves as the Chief Medical Social Media officer for his hospital, has to carefully screen which TikTok challenges he participates in, and the songs he uses with them, to avoid associating his image and that of his profession with something offensive or tasteless. Chiang is informative on TikTok, but he does it while engaging effectively with how people already use the app. And that’s not always something doctors are capable of—or interested in—trying to learn how to do.

“Historically there’s never been any sort of teaching in medical training in how to communicate on a public level with our communities and our patients,” said Chiang.

Online fame takes maintenance and skill to a degree that most people underestimate. And, especially for doctors and other people who work in fields that are targets of disinformation, there are some more serious risks. Chiang points out that some companies will simply steal content from medical professionals on social media and use them to sell their products. And, battling medical misinformation online can make those who believe it angry, potentially endangering the personal safety of doctors who try to take it on.

But Chiang and Varshavski say thesay that the risks are worth it, especially if having more doctors online helps people find better information about their health.

And, as doctors who are both on the internet and treating real patients, they can see how misinformation impacts their patients first-hand. Varshavski treated five covid-19 patients in one recent weekend with mild symptoms, and each asked for hydroxychloroquine, a risky possible treatment that can cause serious heart issues in some patients. Some told Varshavski that they heard about the treatment on TV.