The two-year fight to stop Amazon from selling face recognition to the police

In the summer of 2018, nearly 70 civil rights and research organizations wrote a letter to Jeff Bezos demanding that Amazon stop providing face recognition technology to governments. As part of an increased focus on the role that tech companies were playing in enabling the US government’s tracking and deportation of immigrants, it called on Amazon to “stand up for civil rights and civil liberties.” “As advertised,” it said, “Rekognition is a powerful surveillance system readily available to violate rights and target communities of color.”

Along with the letter, the ACLU Foundation of Washington delivered over 150,000 petition signatures as well as another letter from the company’s own shareholders expressing similar demands. A few days later, Amazon’s employees echoed the concerns in an internal memo.

Despite the mounting pressure, Amazon continued with business as usual. It pushed Rekognition as a tool for monitoring “people of interest” and doubled down on providing other surveillance technologies to governments. The company’s subsidiary Ring, for example, acquired only a few months earlier, rapidly struck up partnerships with more than 1,300 law enforcement agencies to use footage from its home security cameras in criminal investigations.

But on Wednesday, June 10, Amazon shocked civil rights activists and researchers when it announced that it would place a one-year moratorium on police use of Rekognition. The move followed IBM’s decision to discontinue its general-purpose face recognition system. The next day, Microsoft announced that it would stop selling its system to police departments until federal law regulates the technology. While Amazon made the smallest concession of the three companies, it is also the largest provider of the technology to law enforcement. The decision is the culmination of two years of research and external pressure to demonstrate Rekognition’s technical flaws and its potential for abuse.

“It’s incredible that Amazon’s actually responding within this current conversation around racism,” said Deborah Raji, an AI accountability researcher who coauthored a foundational study on the racial biases and inaccuracies built into the company’s technology. “It just speaks to the power of this current moment.”

“A year is a start,” says Kade Crockford, the director of the technology liberty program at the ACLU of Massachusetts. “It is absolutely an admission on the company’s part, at least implicitly, that what racial justice advocates have been telling them for two years is correct: face surveillance technology endangers Black and brown people in the United States. That’s a remarkable admission.”

Two years in the making

In February of 2018, MIT researcher Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, then a Microsoft researcher, published a groundbreaking study called Gender Shades on the gender and racial biases embedded in commercial face recognition systems. At the time, the study included the systems sold by Microsoft, IBM, and Megvii, one of China’s largest face recognition providers. It did not encompass Amazon’s Rekognition.

Nevertheless, it was the first study of its kind, and the results were shocking: the worst system, IBM’s, was 34.4 percentage points worse at classifying gender for dark-skinned women than light-skinned men. The findings immediately debunked the accuracy claims that the companies had been using to sell their products and sparked a debate about face recognition in general.

As the debate raged, it soon became apparent that the problem was also deeper than skewed training data or imperfect algorithms. Even if the systems reached 100% accuracy, they could still be deployed in dangerous ways, many researchers and activists warned.

“There are two ways that this technology can hurt people,” says Raji who worked with Buolamwini and Gebru on Gender Shades. “One way is by not working: by virtue of having higher error rates for people of color, it puts them at greater risk. The second situation is when it does work—where you have the perfect facial recognition system, but it’s easily weaponized against communities to harass them. It’s a separate and connected conversation.”

“The work of Gender Shades was to expose the first situation,” she says. In doing so, it created an opening to expose the second.

Amazon tried to discredit their research; it tried to undermine them as Black women who led this research.

Meredith Whittaker

This is what happened with IBM. After Gender Shades was published, IBM was one of the first companies that reached out to the researchers to figure out how to fix its bias problems. In January of 2019, it released a data set called Diversity in Faces, containing over 1 million annotated face images, in an effort to make such systems better. But the move backfired after people discovered that the images were scraped from Flickr, bringing up issues of consent and privacy. It triggered another series of internal discussions about how to ethically train face recognition. “It led them down the rabbit hole of discovering the multitude of issues that exist with this technology,” Raji says.

So ultimately, it was no surprise when the company finally pulled the plug. (Critics point out that its system didn’t have much of a foothold in the market anyway.) IBM “just realized that the ‘benefits’ were in no way proportional to the harm,” says Raji. “And in this particular moment, it was the right time for them to go public about it.”

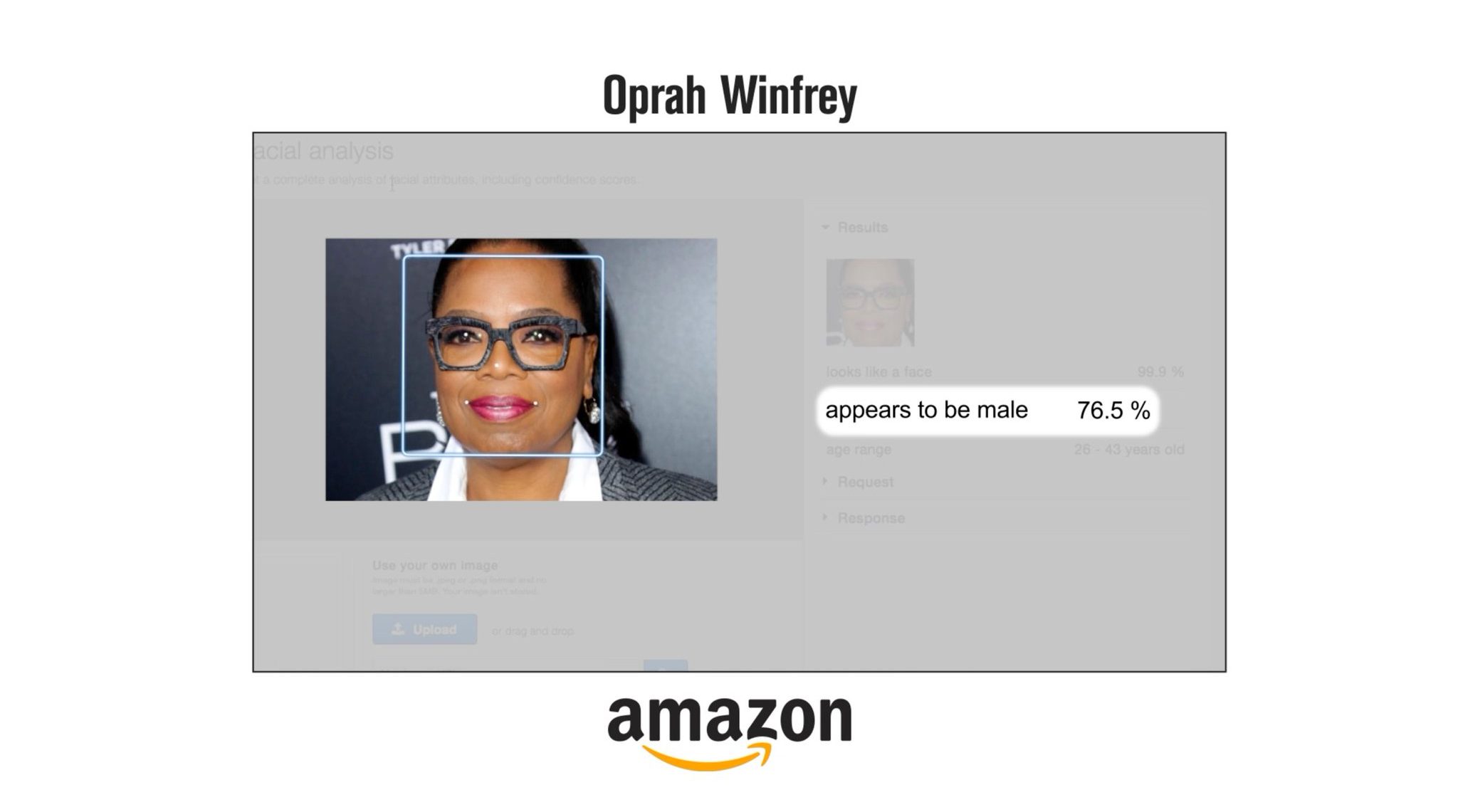

But while IBM was responsive to external feedback, Amazon had the opposite reaction. In June of 2018, in the midst of all the other letters demanding that the company stop police use of Rekognition, Raji and Buolamwini expanded the Gender Shades audit to encompass its performance. The results, published half a year later in a peer-reviewed paper, once again found huge technical inaccuracies. Rekognition was classifying the gender of dark-skinned women 31.4 percentage points less accurately than that of light-skinned men.

In July, the ACLU of Northern California also conducted its own study, finding that the system falsely matched photos of 28 members of the US Congress with mugshots. The false matches were disproportionately people of color.

Rather than acknowledge the results, however, Amazon published two blog posts claiming that Raji and Buolamwini’s work was misleading. In response, nearly 80 AI researchers, including Turing Award winner Yoshua Bengio, defended the work and yet again called for the company to stop selling face recognition to the police.

“It was such an emotional experience at the time,” Raji recalls. “We had done so much due diligence with respect to our results. And then the initial response was so directly confrontational and aggressively defensive.”

“Amazon tried to discredit their research; it tried to undermine them as Black women who led this research,” says Meredith Whittaker, cofounder and director of the AI Now Institute, which studies the social impacts of AI. “It tried to spin up a narrative that they had gotten it wrong—that anyone who understood the tech clearly would know this wasn’t a problem.”

The move really put Amazon in political danger.

Mutale Nkonde

In fact, as it was publicly dismissing the study, Amazon was starting to invest in researching fixes behind the scenes. It hired a fairness lead, invested in an NSF research grant to mitigate the issues, and released a new version of Rekognition a few months later, responding directly to the study’s concerns, Raji says. At the same time, it beat back shareholder efforts to suspend sales of the technology and conduct an independent human rights assessment. It also spent millions lobbying Congress to avoid regulation.

But then everything changed. On May 25, 2020, Officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd, sparking a historic movement in the US to fight institutional racism and end police brutality. In response, House and Senate Democrats introduced a police reform bill that includes a proposal to limit face recognition in a law enforcement context, marking the largest federal effort ever to regulate the technology. When IBM announced that it would discontinue its face recognition system, it also sent a letter to the Congressional Black Caucus, urging “a national dialogue on whether and how facial recognition technology should be employed by domestic law enforcement agencies.”

“I think that IBM’s decision to send that letter, at the time that same legislative body is considering a police reform bill, really shifted the landscape,” says Mutale Nkonde, an AI policy advisor and fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center. “Even though they weren’t a big player in facial recognition, the move really put Amazon in political danger.” It established a clear link between the technology and the ongoing national conversation, in a way that was difficult for regulators to ignore.

A cautious optimism

But while activists and researchers see Amazon’s concession as a major victory, they also recognize that the war isn’t over. For one thing, Amazon’s 102-word announcement was vague on details about whether its moratorium would encompass law enforcement agencies beyond the police, such as US Immigration and Customs Enforcement or the Department of Homeland Security. (Amazon did not respond to a request for comment.) For another, the one-year expiration is also a red flag.

“The cynical part of me says Amazon is going to wait until the protests die down—until the national conversation shifts to something else—to revert to its prior position,” says the ACLU’s Crockford. “We will be watching closely to make sure that these companies aren’t effectively getting good press for these recent announcements while simultaneously working behind the scenes to thwart our efforts in legislatures.”

This is why activists and researchers also believe regulation will play a critical role moving forward. “The lesson here isn’t that companies should self-govern,” says Whittaker. “The lesson is that we need more pressure, and that we need regulations that ensure we’re not just looking at a one-year ban.”

The cynical part of me says Amazon is going to wait until the protests die down…to revert to its prior position.

Kade Crockford

Critics say the stipulations on face recognition in the current police reform bill, which only bans its real-time use in body cameras, aren’t nearly broad enough to hold the tech giants fully accountable. But Nkonde is optimistic: she sees this first set of recommendations as a seed for additional regulation to come. Once passed into law, they will become an important reference point for other bills written to ban face recognition in other applications and contexts.

There’s “really a larger legislative movement” at both the federal and local levels, she says. And the spotlight that Floyd’s death has shined on racist policing practices has accelerated its widespread support.

“It really should not have taken the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and far too many other Black people—and hundreds of thousands of people taking to the streets across the country—for these companies to realize that the demands from Black- and brown-led organizations and scholars, from the ACLU, and from many other groups were morally correct,” Crockford says. “But here we are. Better late than never.”